By Mark Goodson

Implicit bias rises from unconscious beliefs and stereotypes, associations and feelings that we are not even aware of but that impact our day-to-day interactions. These biases can lead to positive outcomes: You strike up a conversation with someone who’s wearing your favorite team’s jersey, and that conversation leads to friendship that lasts for years. But implicit bias can also have difficult, even dire consequences: You’re passed over for a promotion because you’re female, you lose an election because you’re shorter than your opponent, you’re stopped by the police for no apparent reason. Maybe you were stopped simply because you’re Black.

The Prince George’s County Police Department (PGPD) began partnering with the University of Maryland (UMD) in 2012. In 2015, the Presidential Task Force report on 21st century policing recommended in-service implicit bias training for officers, and PGPD Inspector General Carlos Acosta reached out to the university’s Sociology Department for help.

Associate Professor Dr. Kris Marsh responded to Acosta and quickly immersed herself in the police department’s culture. As she went on ride-alongs and joined cookouts, she developed a program to train all 1,700 PGPD officers as part of their mandatory 2018 in-service hours.

Early on in her work, Marsh met Rev. Tony Lee, the founder of Community of Hope A.M.E. Church in Hillcrest Heights. Lee started working with PGPD in 2003, when Melvin High became the department’s chief. Lee described his collaboration with High, and each subsequent chief, as a “community policing thought partnership.”

Lee spoke often with former chief Stawinksi (Stawinski resigned from his position on June 18, 2020). Lee said that Stawinski believed that the implicit bias training could be revolutionary. “He was excited to approach the problem with something that held some sort of academic vigor,” said Lee. “He felt his hands were tied on the administrative side, but something like this [collaborative approach] would be more than just going through the motions.”

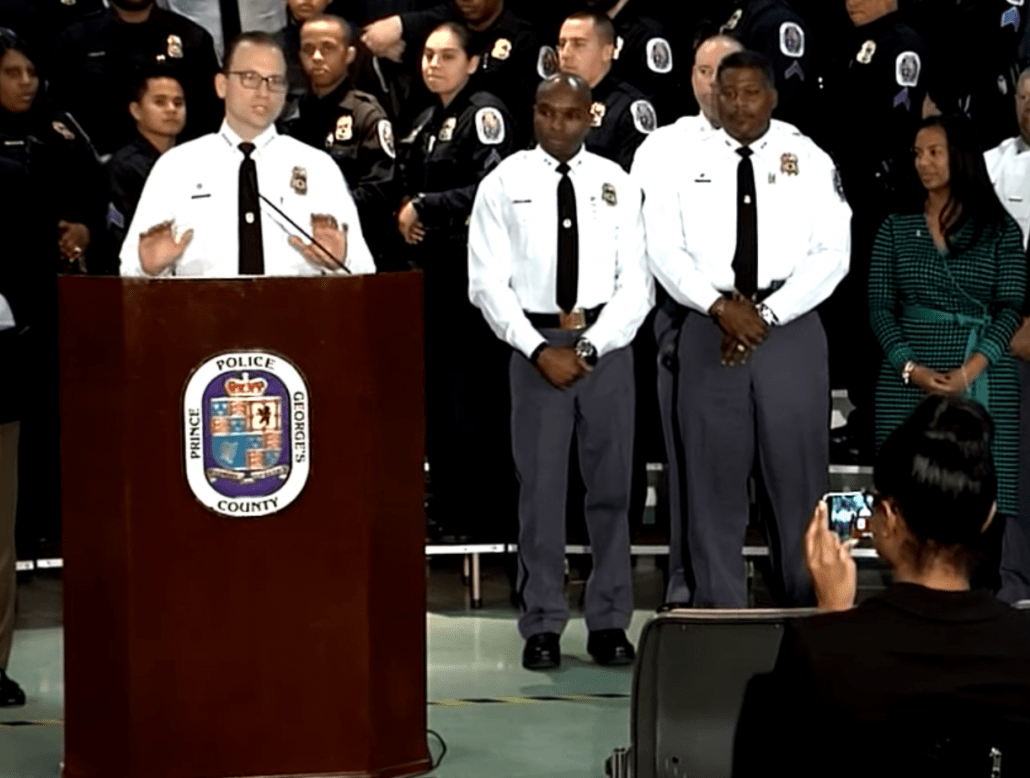

In the 2018 press conference announcing the training program, Stawinski said, “Every decision I make is weighted against how we preserve and enhance the public trust. My long term goal is to change the expectations of this community about the Prince George’s County Police Department.”

It was helpful to have Marsh join in on their conversations, Lee said, adding “We were all attempting, from our different areas, to shape this model of how we can improve policing.”

The course Marsh developed included icebreakers and group discussions designed to increase participants’ awareness of biases they held. Marsh remembers breakthroughs, like when certain officers realized that some of their colleagues couldn’t walk into a drug store and buy a Band-Aid in their own skin tone. Officers also gained insight into the subtlety of their biases by wrestling with activities that pitted Redskins and Cowboys fans against each other.

One active officer who spoke with the Here & Now on the condition of anonymity went through Marsh’s training, in both 2018 and 2019, noted that the training was challenging and uncomfortable at times. “It wasn’t widely received,” he said, adding, “Which probably speaks more to the culture in place.”

As Marsh pressed forward with her training, another side of the PGPD came into the spotlight. In December 2018, the United States District Court for the District of Maryland, on behalf of several plaintiffs, charged the department with condoning racist conduct described as “persistent.”

That officer who chose to remain anonymous, due to the sensitive nature of this reporting, described the PGCPS culture as imbued with “cronyism” and “nepotism.” Of Dr. Marsh’s efforts, he said, “She was completely professional and intentional in her approach, defining racism as a system, as opposed to the traditional definition of an overt act.” The officer added, “For a woman to come into a male work environment, it’s a lion’s den, especially considering all the prejudices and biases that have been well documented.”

This is the sort of reaction Marsh, Lee and Stawinski were looking for, Lee said. He added that Stawinski told him that the department needed to do more transformational things like this in order to grow, and acknowledged that growth can be difficult.

This is the third year that Marsh’s implicit bias training has been a mandatory component of PGPD’s training. Partnering with a university makes this training a pioneering endeavor in the DMV, according to Jennifer Donlean, former PGPD media relations manager.

“I do recall there being some hiccups at the start,” she added.

In 2018, Marsh’s colleague Dr. Rashawn Ray was conducting police training at the university. Ray is a professor in the university’s Department of Sociology and executive director of the Lab for Applied Social Science Research.

Several sources confirmed that many officers in Ray’s training were uncomfortable.

While the classroom training was mandatory, officers had the option of voluntarily participating in a virtual reality simulator which required them to sign a waiver permitting data collection. When officers expressed misgivings that data was being collected, former police chief Stawinski began coming to the sessions to explain the data collection, which was not mandatory. Marsh said, “Every Tuesday morning, he would come in and say, ‘be respectful, listen. This will make us better officers.’”

Officers at the June 5, 2018 training were particularly uncomfortable that unidentified people were observing the session. Sergeant Kevin McSwain, who oversaw advanced officer training for the PGPD in 2018, said that officers were concerned that the unidentified students might record the training on their computers or phones, which would be in violation of Maryland’s two-party consent laws.

In an email to Ray and others, McSwain wrote, “To address this issue, please advise all interns that this training is a part of the officers in-service training and therefore precludes unauthorized individuals from attending without expressed permission for the Prince Georges County Chief of Police.”

McSwain said that he did not receive a response to his email. Unidentified people were again present at a training one week later, on June 12. Officers at that training contacted McSwain during a break, and he gave them permission to leave.

“I focused on protecting the troops,” said McSwain. “That was my job.”

NBC4 broke an exclusive story on the incident, claiming that officers walked out of the training because department leadership discouraged them from completing it.

McSwain said, “The training wasn’t the issue. The issue was the unidentified persons present and the [possible] collection of data.”

“There was no walkout,” said Jennifer Donelan, former PGPD media relations manager. “Certain criteria that had been agreed upon between the university and the department was not being honored by Professor Ray.”

When the news of Stawinksi’s resignation broke on June 18 of this year, NBC4 cited its exclusive reporting of the incident at the training on June 12, 2018. Ray told NBC4, “We have one of the most innovative police decision-making programs in the United States based on our corporate sponsors, and they chose not to use it,” referring to the virtual reality simulator.

After the issues with data collection, Ray stopped training officers, but the training program continued. The department moved the bias training to its own facility, with the intent of reassuring officers that their data would not be collected. Marsh became the sole instructor.

Entrusting training to a civilian unaffiliated with the police, like Marsh, was a first in McSwain’s 29 years of duty. “It gives us a different approach to understand how we are viewed,” he said.

Collaborating to create this training was something that excited Lee, Stawinksi and Marsh. According to Lee, they even discussed collaborating on a book about transforming community policing. Of the media coverage, Lee said, “I am concerned that the intentions of some of these programs and involvement of the police department are not being fairly depicted.”

Marsh’s 2020 program focuses on the impact of social media. Helpful training, no doubt, because police, who routinely conduct themselves in the public eye, are also subject to the court of popular opinion.

Dr. Ray did not reply to a request for an interview from the College Park Here & Now.