BY RANDY FLETCHER

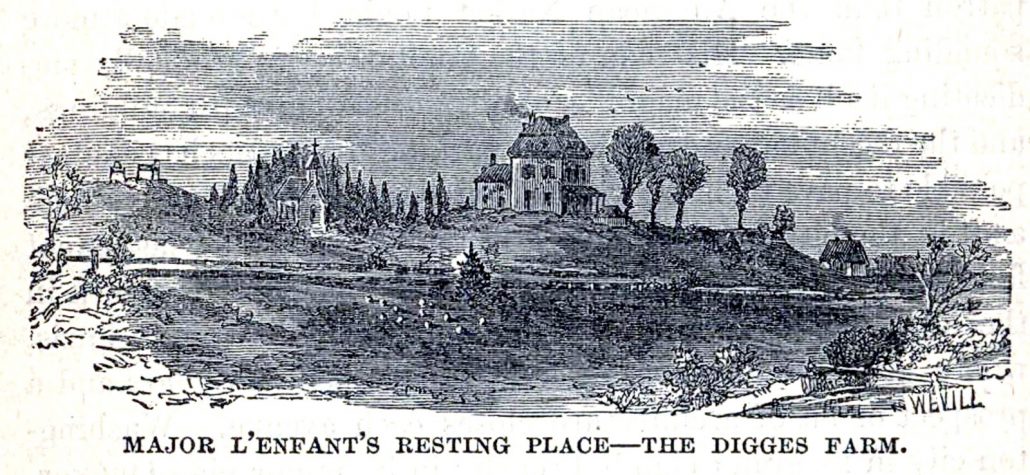

High on a hill, overlooking the newly designed federal city, which he had helped to conceive, lay the remains of Major Pierre Charles L’Enfant. His body was buried in a grove of newly planted red cedars, in the back garden of his dear friend William Dudley Digges on June 14, 1825. His remains would lie there, undisturbed and unrecognized, for nearly a century.

Photo credit: Randy Fletcher

In 1791, George Washington chose L’Enfant, the premier engineer and architect of the day, to plan the layout of Washington City, which makes up the core of what we now know as Washington, D.C. L’Enfant was highly sought after and had received major commissions in New York and Philadelphia. He also designed furniture, coins and medals, including the Purple Heart medal.

Despite this acclaim, L’Enfant eventually lost it all. Evidently, he was difficult to work with, quarreled all the time, and was ultimately fired from his commissions. This disgrace led to a slide into poverty. In his later life, he was often seen pacing the floors of the Capitol Building, carrying scrolls of papers under his arms and swinging a large hickory cane with a silver head. Right up until his death, L’Enfant insisted that he was not paid enough for his contribution to the layout of the city.

Meanwhile, L’Enfant’s friend W.D. Digges invited the angry old man to visit his home, which was built in the early 19th century and substantially enlarged by the Riggs family in the late 19th century. It was known as Chillum Castle Manor after Digges’ ancestral home in Kent County, England. L’Enfant became a permanent house guest, and we now know he never left until long after his death. The manor house, which is also known as Green Hill, is still there, hidden in Lewisdale on the hill at the intersection of East-West Highway and Riggs Road, behind a strip mall.

It was at this time of year about a decade ago that I first noticed the manor. The leaves had mostly fallen from the trees, and I caught a glimpse of the gleaming white ionic columns hiding in the woods. I soon learned that Chillum Castle Manor is now headquarters for the Pallottine Seminary. After doing some digging, I discovered the sad story behind L’Enfant’s current fame.

For 84 years, L’Enfant was all but forgotten. However, at the turn of the century, an article about him appeared in the New-York Tribune. The French ambassador, Jean Jules Jusserand, who was also a friend of Theodore Roosevelt, wrote a biography of L’Enfant, which reminded people of this Revolutionary War hero and designer of the basic layout of Washington, D.C.

In 1908, Congress approved funds to have L’Enfant’s body removed from the old manor and interred in a place that would be accessible to the public. The U.S. secretary of war approved a prime gravesite in Arlington National Cemetery.

As the story goes, workers tasked with exhuming his body found a lonely and unmarked grave, surrounded by red cedars. The trees stood as the sole monument marking the resting place of the neglected Frenchman. They sheltered the grave, swaying in the breeze so their perpetual incense perfumed the mound of moss covering the major’s remains. As their shovels began moving the soft earth, the workers found that the roots of a cedar had enveloped the major’s body. The cedar was cut, and the decayed coffin was liberated from its roots. The macabre scene was described in Michael Kammen’s Digging up the Dead: “Witnesses found that a badly decomposed coffin with a layer of discolored mold three inches in thickness, two pieces of bone, and a tooth were all that remained of the great engineer.” A root from the red cedar was saved and later carved into a gavel, which was presented to the Columbia Historical Society, now known as the DC History Center.

This story brings to mind a verse from the poem “In Memoriam” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson:

Old Yew, which graspest at the stones

That name the under-lying dead,

Thy fibres net the dreamless head,

Thy roots are wrapt about the bones …

L’Enfant’s remains were gathered, placed in a metal casket, and taken to Mount Olivet Cemetery. From there he was brought to the Capitol Rotunda, his casket draped with the American flag. It was placed on the catafalque (platform) that had supported the coffin of Abraham Lincoln. L’Enfant became the first foreign-born person, and the ninth individual, to be given such a high honor.

Pomp finally came to L’Enfant in 1909, and he was given his due. Just 10 miles from his original unmarked grave high on a hill, he was interred in his new resting place, also high on a hill, at Arlington Cemetery, with a beautiful view of the city he helped design.

“Then & Now” is a column about houses and history in the Hyattsville area.